It wasn’t so much about the announcement or the declaration of death, muttered Qaiser, but the hours, minutes and seconds between the knowing and the not knowing — the brief yet interminable time of feeling suspended. On Tuesday, the elderly, bespectacled man entered his fourth day of waiting outside what used to be Gul Plaza.

Patches of dust, soot and perspiration stained his white shalwar kameez. His eyes drifted everywhere all at once, always searching but never landing anywhere. Every time a reporter approached him for an interview, he traded it for information: “Here is my phone number, please share the list of the dead whenever you get it,” he requested, and then proceeded to narrate his story.

“My begum loved to shop, and she found the perfect partners in my daughter and bahu,” Qaiser recalled. On Saturday evening, the three women ventured to Gul Plaza — a paradise for shopaholics in Karachi — with a strict 10pm curfew. It was broken, and since then, Qaiser had remained encamped in front of the shopping centre.

As of Wednesday, dozens of people who were trapped inside the plaza when the fire erupted were still missing. So far, 67 bodies or their remains had been recovered.

Outside Gul Plaza — now just an empty shell — fire trucks and water tankers stood close by, sporadically spraying water to cool the thick smoke emanating from the building. At a short distance, Edhi and Chhipa ambulances lined the road, the drivers inside them taking turns to rest their backs. Near the rear end of the mall, which had since caved in, dumper trucks made hourly rounds to clear carcasses and debris.

On the main road facing the plaza, a crowd of spectators had converged on the footpath, watching intently; dozens of others stood on the rooftops of nearby buildings to get a better view. Camps had also been set up nearby, and the volunteers seated there were quick to distribute water bottles to firefighters, policemen and rescue officials.

Movement never eluded Gul Plaza — not in life, nor in death. But even as rescue work continued, the air hung heavy with the weight of the wait, suspended in anticipation like a defendant about to hear the verdict.

Waiting for help to arrive

For Muhammad Shujat, who worked at an electronics shop at the plaza, patience was running thin on the fourth day. “It is better to die once than to die 100 times each waiting minute,” his shrill cry echoed through the morning breeze. “It is agony.”

Like Qaiser, he hadn’t been home since late Saturday night. He recalled leaving his shop “fully intact” at 9:30pm — the shutters were locked and the day’s earnings secured. “Around 10:45pm, I started getting calls that a fire had erupted at Gul Plaza.”

The 40-year-old reached the plaza within 15 minutes from his residence in Orangi Town, otherwise a 45-minute drive, where he was welcomed by chaos, screams and tears — all of which had been playing inside his brain on loop.

“I tried to get into my shop, which faces the main road, and frantically tried to secure the merchandise, but the flames were huge, unforgiving. All I could do instead was watch my livelihood burn before me and wait … wait for fire tenders, for divine intervention, for a miracle.”

Help did come, but a little too late. The first tenders arrived at the site nearly two hours after the fire broke out, Shujat recalled, and within five minutes they ran out of water. “Once again, we were told to wait, this time for water tankers that were coming from Sohrab Goth and Nipa Chowrangi.”

But by the time they arrived, Shujat’s shop — which, according to him, held items worth Rs3 billion — was reduced to ashes. There was nothing left to save.

“Theek hai [that’s fine],” he said. “They were merely objects, merely money, merely materials that can be built again … but what about the people? Faisal sahab, the neighbour; Asif sahab, the friend; Usman and Kamran, the porters — who will bring them back?”

Shujat’s remarks were not rhetorical; they were very much a question. He was waiting for them, even if dead, and he was ready to risk his life to get them out. “I am tired of waiting. I am ready to jump inside if I have to. I need them back.”

As he spoke, Shujat’s voice pitched higher, loud enough to attract the attention of policemen and Rangers personnel on duty. They began closing in on him to prevent any potential commotion, but before that could happen, Qaiser jumped in.

“Bhai, even I am frustrated … but we must wait,” he coaxed the fellow griever and then proceeded to embrace Shujat, who broke down instantly. Both found a spot at the footpath and sat together, waiting.

Waiting for empathy

A few steps from them, two men in yellow jackets inscribed with ‘Khidmat-i-Khalq Foundation’ walked back to a fire truck owned by the welfare organisation.

“It is hell inside … 100 degrees Celsius,” one of them announced.

“The building will fall … the walls are cracking, they are withering … sab kuch jal k raakh hogaya hai,” said the other.

Among them was Muhammad Khizer Khan, the head of the foundation’s Karachi division and one of the first to arrive at Gul Plaza that night. “On reaching the site, we got our fire trucks working,” he recounted to Dawn.

But what fight could two vehicles put up against a monster breathing flames?

According to his team’s findings, the fire broke out in the air conditioning unit and then spread toward the artificial flower shops on the mezzanine floor. “After waiting for two hours, when the KMC (Karachi Metropolitan Corporation) fire trucks finally arrived, they did not have snorkels, so the blaze on the top floors was not catered to.”

During every minute spent waiting, the fire gained strength, intensity, and control — eventually, it became a third-degree blaze. “Every time, we wait for the government to come up with a better response, every time we wait for them to act promptly, every time we fall for the empty promises they make to us.”

Suddenly, an announcement was made. A body was found, but it was unidentifiable — just bones. The engine of one of the Chhipa ambulances revved; the vehicle bounced over the road dug up for the rapid bus transit construction, off to the Dr Ruth Pfau Civil Hospital. Several people, including Qaiser and Shujat, gathered, shooting questions, but they were all told to head to the medical facility and get DNA tests done. Chaos ensued.

Ehsan Waleed, whose cousin was missing, was among those searching. “We keep running here and there … when we go up to them, they tell us to wait; when we ask questions, they tell us to calm down. What do we do?” he asked.

“From the first day, we have been telling rescue officials to set up an information desk here (there is one at the district commissioner’s office) to facilitate and guide the families.

“They said they will. We are all still waiting.”

When the men in uniforms wait

For his part, Javed Irshad, deputy director of the KMC Fire Brigade, told Dawn that the department received a call regarding the Gul Plaza inferno a little after 10:30pm. In seven minutes, three fire trucks, each accompanied by a nine-member crew, were deployed.

“Our response time for any such incident is three minutes, which means that during this time span, the fire trucks and crew must be out of the station,” he explained. “But we cannot tell when it reaches the site because there are multiple factors at play, such as traffic jams, the condition of the roads …

“All of Karachi is dug up,” Irshad scoffed. The road opposite Gul Plaza was no different.

On reaching the site, an examination was conducted to check the connection points for water lines, turn off the electricity, and inspect the building. “But by that time, the fire had intensified to unprecedented levels; in my 36 years of experience, never have I seen this.”

He admitted that the fire trucks ran out of water, which then had to be summoned from the Karachi Water and Sewage Corporation-run hydrants, all located at a considerable distance from the site. “These are all operational challenges that we don’t have any control over; this doesn’t raise questions about our firefighters, their valour or bravery.”

“And they demonstrated this when they stepped inside the building despite extreme heat, when they remained calm even after being mistreated, and when our firefighter lost his life during the rescue operation,” Irshad added.

Rescue 1122 spokesperson Hassaanul Haseeb Khan narrated similar challenges during the operation: broken roads and traffic jams delayed the emergency response. “And when we reached the plaza, the entire area was jammed packed due to the weekend … to top it, a mob-like situation emerged.”

When the fire trucks ran out of water, it wasn’t just the people who were waiting, but Haseeb and his team did too. “As the intensity of the fire increased, we knew how difficult it would be to control it … but we could do nothing about the traffic or the broken roads or the narrow lanes or the people who just wanted to save their shops.”

Waiting for resources

At the same time, Irshad acknowledged the need for a bigger staff and better resources for the fire department.

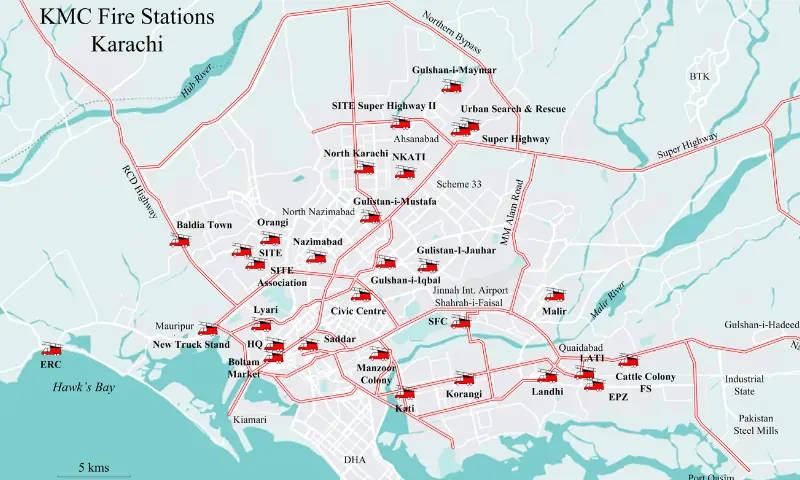

According to international fire safety protocols, there must be one fire station for a population of 100,000. In Karachi — home to over 20 million as per the 2023 census — a meagre 28 fire stations are functional, which isn’t sufficient to meet even 10 per cent of the metropolis’ needs.

Ideally, every locality in the city should have a fire station with two fire trucks on service. During a Sindh Assembly session last month, it was revealed that Karachi only has 36 fire tenders, four snorkels and roughly 700 staff, when it actually needs about 200 stations and 34,000 staff.

The Sindh government tried to purchase 89 fire tenders in 2021, with 17 originally allocated to Karachi. The order was reduced to 35 vehicles, and Karachi’s share was cut and redistributed across the province to Hyderabad (10), Sukkur (7), Benazirabad (5), Mirpurkhas (5), and Larkana (8). None of them, however, has been delivered.

During the Gul Plaza inferno, the absence of this equipment manifested in the worst way possible. Haseeb of Rescue 1122 mentioned how lighting was a key issue as his men worked in near-total darkness, trying to navigate through narrow stairwells.

“We are sifting through every particle of dust and ash here … we are looking for not just a human body but body parts,” he said.

Meanwhile, Syed Mairaj Mohsin, a Chhipa worker who had been on duty outside the shopping centre since Saturday, pointed out how window grills prevented people from escaping. “We have seen these visuals at the Baldia factory fire and the RJ Mall inferno.”

In the current scenario, Karachi needed all of the city’s fire tenders to deal with a third-degree fire, such as the one at Gul Plaza, which was exactly what happened. If the city were to face another such blaze, it would need Rs5 billion to equip the fire department, showed a batch of official documents available with Dawn.

What we are talking about here is basic equipment: adequate water supply, wireless communication tools, lighting, the right vehicles, fire suits for each man that usually cost $2,500 or Rs700,000, breathing apparatus, protective masks, helmets, hydraulic cutters and spreaders, and smoke ejectors. In their absence, it was not possible to safely enter burning structures or remain inside long enough to rescue people.

Irshad was hopeful, though. He called the Karachi Fire Department Mayor Murtaza Wahab’s ‘favourite’. “He has promised to fill 440 vacancies for firemen and drivers within two months. At the same time, promotions in the department, halted for a long time, are also on the cards,” he was confident.

Waiting for prevention

Meanwhile, for Sufyan Sheikh, secretary general of the Fire Protection Association of Pakistan, the tragedy at Gul Plaza cannot be fully understood through the lens of a delayed response.

“Globally, the fire brigade is considered the last line of defence,” he explained. “Before that, the responsibility lies squarely with building owners.”

A fire tender, Sheikh said, could carry roughly 3,000 gallons of water — enough to douse flames for just two to two-and-a-half minutes — provided the water was released at a pressure of 500 gallons per minute at eight bar. “It is not technically possible for a fire truck to carry more than that,” he added.

“Ideally, every locality should have its own fire station,” Sheikh said. “For sustained firefighting, you need at least 60,000 gallons of water for two hours. With these resources, how do you give coverage to the entire city?”

The Gul Plaza inferno, he pointed out, was one of the few incidents where almost all available firefighting machinery in Karachi was deployed — and even then, it took three days to extinguish the blaze. “What if two such fires break out at the same time?” he asked. “What will you do then?”

Sheikh believed the greater failure lies not in response, but in prevention.

International standards require building owners to take extensive fire safety measures, including the installation of functional extinguishers, clearly marked and accessible emergency exits, fire alarms, proper housekeeping of combustible materials, and adherence to occupancy limits. “If these measures are in place, the intensity of a fire can be reduced by up to 95pc,” he said.

Those who were unable to escape Gul Plaza, he added, were largely people who stayed behind to protect their shops, only to be eventually trapped. “A third-degree fire produces temperatures of up to 1,000 degrees Celsius. You cannot expect firefighters to go inside such conditions,” Sheikh said. “It is simply not possible.”

What was needed now, he stressed, were structural reforms: stricter enforcement of building safety codes, the hiring of competent inspection teams, and sustained public education on fire risks. “The government can fix this,” he said. “The real question is whether it wants to.”

Until then, the waiting continues — outside Gul Plaza, where men like Qaiser and Shujat remain on the footpath, watching ambulances come and go, listening for announcements that may finally bring certainty.

In Karachi, waiting has become part of the disaster itself: waiting for water, for help, for answers, for reforms. And in that waiting, lives are lost not all at once, but with each passing minute.

Header image: What remains of the main entrance of Gul Plaza after a deadly fire ripped through the shopping centre. — all photos by author