During a seminar organised by the Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Crop Production at Sindh Agriculture University, Tandojam, national and international experts cautioned that Pakistan’s soil health is deteriorating at an alarming pace due to excessive and indiscriminate use of chemical fertilizers. They stressed the urgent need for regenerative agriculture, biodiversity restoration, and compost-based solutions to secure sustainable farming for future generations

This past month, heavy monsoon rains have swept through the country, causing flooding. These floods add a complex layer to the soil health crisis. “After floods, agriculture fields in many areas are buried under layers of sand, sediments and silt, while the fertile topsoil is washed away,” said Dr. Babar Shahbaz, Director of the Institute of Agricultural Extension, Education and Rural Development at the University of Agriculture, Faisalabad. “Prolonged waterlogging also destroys soil microbes and organic matter”.

Shahbaz warned that farmers’ reliance on excessive chemical fertilizers without soil testing, as well as the burning of crop residues, is stripping fields of vital nutrients. “Continuous cultivation of nutrient-intensive crops like wheat, rice, and maize without rotation has depleted essential nutrients in the soil,” he said. Interestingly enough, the antidote to this may lie in the very calamity we often demonise. The floods carry particles that are essential for the soil’s nutrient profile. “When deposited on flood plains, these sediments can enrich soils with fresh nutrients such as potassium, magnesium, calcium and micronutrients,” said Prof. Dr. Altaf Siyal, acting Vice Chancellor of Sindh Agriculture University, Tandojam. “In some cases, organic matter from decayed plants or animal residues in floodwater adds humus, improving soil fertility in the short term”.

Floods function as a natural phenomenon that revitalises the soil. “Floods deposit fine alluvium that replenishes the soil profile,” Siyal added. “They can also recharge groundwater supplies and leave the soil well hydrated for the next cropping cycle”. This forces us to consider the fact that floods themselves are not inherently destructive to the natural world. If nonresilient housing is constructed over floodplains, the destruction is a matter of course. These areas have been subject to flooding for centuries and have maintained their fertility.

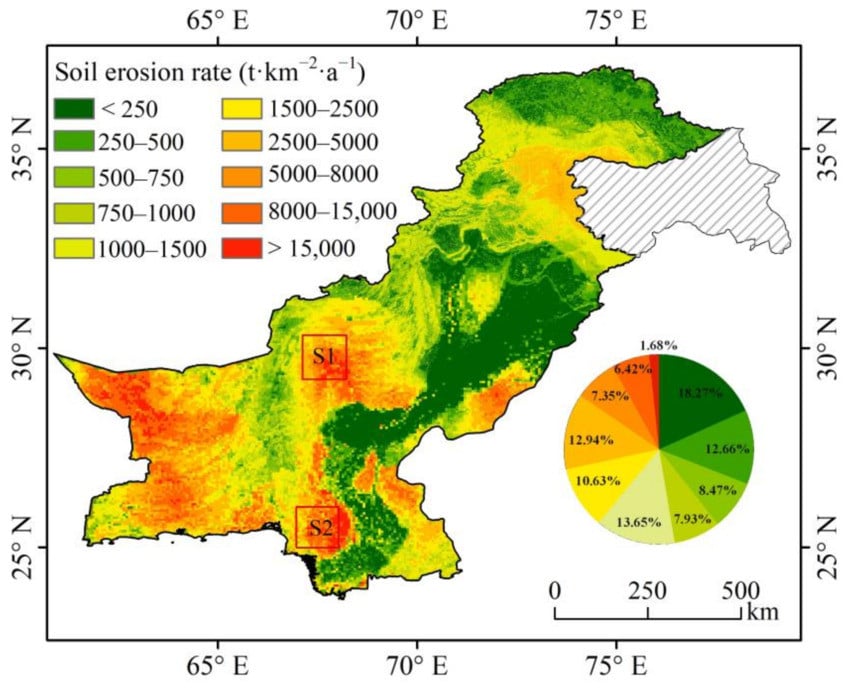

The reasons for soil degradation are multifold. “Soil erosion, poor irrigation practices, salinity, waterlogging, overgrazing, and unsustainable agricultural practices are rapidly degrading Pakistan’s soil,” said Shahbaz Both. Siyal and Shahbaz stressed that burning rice crop residues in Punjab and excessive irrigation in Sindh are worsening the problem. Shahbaz mentioned that burning residue deteriorates soil health by depleting organic matter and essential nutrients and by killing beneficial soil microbes.

Both. Siyal and Shahbaz stressed that burning rice crop residues in Punjab and excessive irrigation in Sindh are worsening the problem. Shahbaz mentioned that burning residue deteriorates soil health by depleting organic matter and essential nutrients and by killing beneficial soil microbes.

“Healthy soil is the lifeblood for higher crop yield, food security, livelihoods, and ecosystem services. If soil degrades, Pakistan’s capacity to feed its growing population will be at serious risk,” said Siyal.

Read: Experts urge shift to regenerative farming

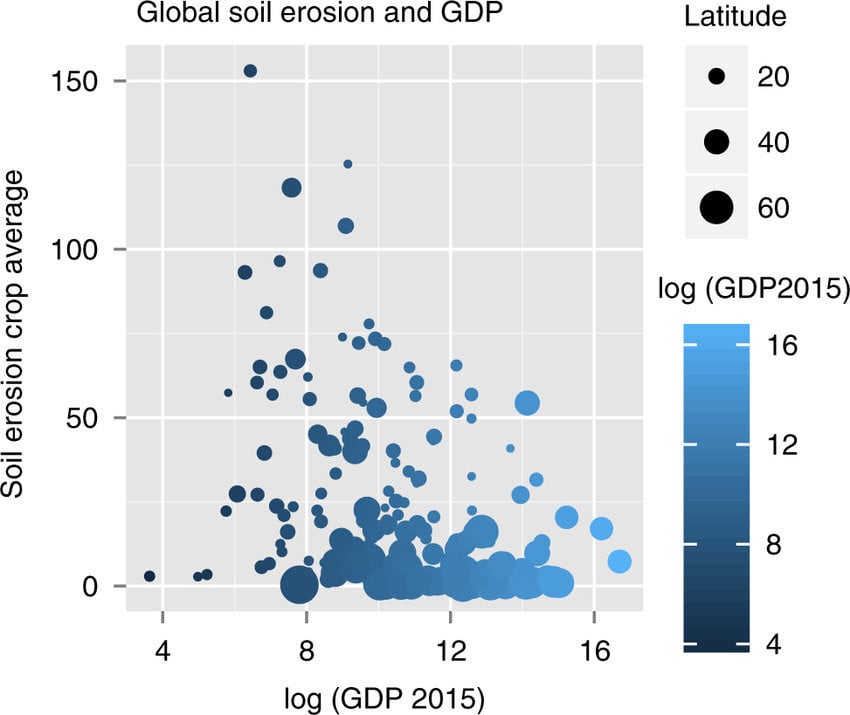

The loss in soil quality is not just an environmental concern. “Pakistan is losing an estimated 1.5–2% of its agricultural GDP annually due to soil degradation,” said Siyal. “In Sindh alone, more than 2 million hectares are affected by salinity and sodicity, demanding immediate rehabilitation”.

Siyal linked poor soil management directly to economic losses. As for solutions, Shahbaz said, “We need to increase the use of bio-fertilizers, farmyard manure, compost and adopt crop diversification, minimum tillage, and high-efficiency irrigation systems”.

Siyal echoed the urgency of moving towards regenerative practices. “Regenerative farming offers sustainable solutions to rebuild soil organic matter, improve nutrient cycling, and restore ecology and microbial biodiversity,” he said.

With experts urging immediate action, the challenge now lies in how quickly Pakistan can pivot toward sustainable practices. The choice between short-term fixes and long-term resilience may well decide the future of the country’s soil and its ability to feed generations to come.