KHARO CHAN: Salt crusts crackle underfoot as Habibullah Khatti walks to his mother’s grave to say a final goodbye before he abandons his parched island village on Indus delta.

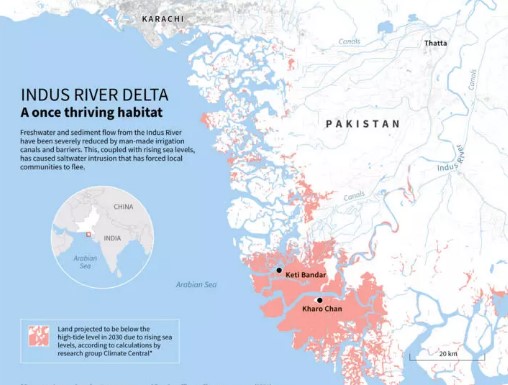

Seawater intrusion into the delta, where the Indus River meets the Arabian Sea in the south of the country, has triggered the collapse of farming and fishing communities.

“The saline water has surrounded us from all four sides,” Khatti told AFP from Abdullah Mirbahar village in the town of Kharo Chan, around 15 kilometres (9 miles) from where the river empties into the sea.

As fish stocks fell, the 54-year-old turned to tailoring until that too became impossible, with only four of the 150 households remaining. “In the evening, an eerie silence takes over the area,” he said, as stray dogs wandered through the deserted wooden and bamboo houses.

Kharo Chan once comprised around 40 villages, but most have disappeared under rising seawater. The town’s population fell from 26,000 in 1981 to 11,000 in 2023, according to census data.

Khatti is preparing to move his family to nearby Karachi, Pakistan’s largest city, and one swelling with economic migrants, including from the Indus delta.

The Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum, which advocates for fishing communities, estimates that tens of thousands of people have been displaced from the delta’s coastal districts.

However, more than 1.2 million people have been displaced from the overall Indus delta region in the last two decades, according to a study published in March by the Jinnah Institute, a think tank led by a former climate change minister.

The downstream flow of water into the delta has decreased by 80% since the 1950s as a result of irrigation canals, hydropower dams and the impacts of climate change on glacial and snow melt, according to a 2018 study by the US-Pakistan Centre for Advanced Studies in Water.

That has led to devastating seawater intrusion.

The salinity of the water has risen by around 70% since 1990, making it impossible to grow crops and severely affecting the shrimp and crab populations.

“The delta is both sinking and shrinking,” said Muhammad Ali Anjum, a local WWF conservationist.

Rising water level

Beginning in Tibet, the Indus River flows through Kashmir before traversing the entire length of Pakistan. The river and its tributaries irrigate about 80% of the country’s farmland, supporting millions of livelihoods.

The delta, formed by rich sediment deposited by the river as it meets the sea, was once ideal for farming, fishing, mangroves and wildlife.

But more than 16% of fertile land has become unproductive due to encroaching seawater, a government water agency study in 2019 found.

In the town of Keti Bandar, which spreads inland from the water’s edge, a white layer of salt crystals covers the ground. Boats carry in drinkable water from miles away, and villagers cart it home via donkeys.

“Who leaves their homeland willingly?” said Haji Karam Jat, whose house was swallowed by the rising water level.

He rebuilt farther inland, anticipating more families would join him.

“A person only leaves their motherland when they have no other choice,” he told AFP.

Way of life lost

British colonial rulers were the first to alter the course of the Indus River with canals and dams, followed more recently by dozens of hydropower projects. Earlier this year, several canal projects on the Indus River were halted when farmers in the low-lying riverine areas of Sindh province protested.

To combat the degradation of the Indus River Basin, the government and the United Nations launched the “Living Indus Initiative” in 2021. One intervention focuses on restoring the delta by addressing soil salinity and protecting local agriculture and ecosystems.

The Sindh government is currently running its own mangrove restoration project, aiming to revive forests that serve as a natural barrier against saltwater intrusion.

Even as mangroves are restored in some parts of the coastline, land grabbing and residential development projects drive clearing in other areas.

Neighbouring India meanwhile poses a looming threat to the river and its delta, after revoking a 1960 water treaty with Pakistan which divides control over the Indus basin rivers.

It has threatened to never reinstate the treaty and build dams upstream, squeezing the flow of water to Pakistan, which has called it “an act of war”.

Alongside their homes, the communities have lost a way of life tightly bound up in the delta, said climate activist Fatima Majeed, who works with the Pakistan Fisherfolk Forum.

Women, in particular, who for generations have stitched nets and packed the day’s catches, struggle to find work when they migrate to cities, said Majeed, whose grandfather relocated the family from Kharo Chan to the outskirts of Karachi.

“We haven’t just lost our land, we’ve lost our culture,” he remarked.