Pakistan and the Paris promise: On the wrong side of 1.5°C

Ten years after the signing of the Paris Agreement, Pakistan faces an uncomfortable truth: we are steadily moving towards a climate future we were meant to avoid.

For decades, Pakistan’s engagement with the annual UN climate summits — the COPs — has revolved around a single question: how much money are we going to get? Our success or failure at these negotiations has thus been measured by the size of the financial commitments pledged by developed countries to developing ones.

The fight for climate safety

When COP27 established the Loss and Damage Fund, Pakistan — then chairing the G77 — rightly celebrated it as a diplomatic victory. Yet, our climate diplomacy remains trapped within a narrow frame of finance and compensation, while paying little attention to the far greater challenge of halting the emissions that are driving the crisis itself.

This imbalance carries grave, devastating stakes. Pakistan is one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable countries. At the current level of global warming — estimated at about 1.34 degrees above pre-industrial temperatures — the country is already witnessing a cascade of climate-induced disasters. Floods, droughts, and prolonged heatwaves have become recurring events, glaciers in the north are retreating at alarming rates, and rising sea levels are encroaching upon coastal settlements.

One does not need to be a climate scientist to imagine what lies ahead if global temperatures exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5 degree limit. For a country as exposed as Pakistan, every fraction of a degree translates into tangible loss of livelihoods, ecosystems, and lives. The path to safety therefore lies not in compensation alone, but in mitigation and the collective effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The decade since the Paris Agreement presents a mixed picture of progress and failure. On one hand, there are reasons for cautious optimism. A recent report by the international think tank Climate Analytics notes that since 2015, many countries have moved from fragmented and sector-specific targets to comprehensive, economy-wide emission reduction goals.

As a result, projections for this century show a marked decline in expected emissions, with anticipated warming by the year 2100 falling from roughly 3.6°C before the Paris Agreement to about 2.7°C under current policies. Avoiding that one extra degree means fewer heatwaves, less sea-level rise, and a lower risk of crossing dangerous climate tipping points.

The Paris Agreement has also triggered a historic shift in global investment trends. Clean energy technologies now attract more than two trillion dollars in investment each year, which is more than double the amount still directed towards fossil fuels. For every dollar spent on oil, coal, or gas, nearly two dollars are now being invested in renewables.

Following the landmark advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice, the 1.5°C target has become both the moral and scientific foundation of global climate policy. Meanwhile, the Loss and Damage Fund is being operationalised, climate litigation is expanding across jurisdictions, and cities, regions, and civil society networks are advancing Paris-aligned actions where national governments have been slow to act.

Yet despite these developments, global ambition continues to fall short of what is required. Even if all existing national pledges, like the Nationally Determined Contributions, are fully implemented, the planet remains on course for between 2.3 and 2.5°C of warming by the end of the century. Years of delayed action have already added about 0.1°C of additional warming since 2015, making it increasingly unlikely that we can limit the rise to 1.5 degrees without overshoot.

Because global emissions failed to peak during the past decade, scientists now consider a temporary breach of the 1.5°C threshold to be almost inevitable. The extent of that overshoot will determine how much irreversible damage the world suffers. A sustained rise of even 0.4 degrees beyond the target could push many glaciers past the point of recovery and unleash losses that no amount of future adaptation can undo.

Survival demands more than diplomacy

For Pakistan, this global trajectory is deeply worrying.

Given the country’s extreme vulnerability, one would expect Pakistan to be among the most vocal defenders of the 1.5°C target. Instead, its position has remained ambiguous and subdued, shaped less by scientific urgency and more by geopolitical alignment.

As a member of the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group — a bloc that includes China, India, and Saudi Arabia — Pakistan has tended to echo the priorities of economies that remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels. These countries publicly endorse the Paris goals, yet often invoke the principles of “equity” and “historical responsibility” to justify a slower transition away from carbon. In doing so, they weaken collective ambition, and Pakistan has followed the same path.

Our domestic choices tell a similar story. Over the past decade, Pakistan has continued to invest in coal and imported liquefied natural gas, locking its energy system into dependence on expensive and polluting fuels. At the same time, ordinary citizens have begun their own quiet transition.

With the falling price of solar technology, more and more households are turning to rooftop solar systems and batteries, reducing their reliance on the national grid. Instead of supporting this encouraging trend, policymakers have sought to slow it down, citing the rising circular debt in the power sector, a problem rooted not in solar power but in years of mismanagement and short-sighted planning.

Today, Pakistan stands at the intersection of three converging crises: escalating temperatures, geopolitical inertia, and a fragile power sector. To continue treating climate action as a bargaining chip in international negotiations is no longer sustainable.

As a democratic republic, our foremost responsibility is to safeguard our people from the worsening impact of climate change. That requires reclaiming our climate leadership, not merely as a victim seeking aid, but as a country willing to act, a nation that defends the 1.5 degree goal as a matter of survival and aligns its domestic energy policies with that vision.

Whether Pakistan chooses that path at the next COP remains to be seen. But time is running out.

The world will not wait for us to find our footing. We can either remain on the wrong side of the Paris promise or recognise, before it is too late, that keeping the 1.5 degree goal alive is not a diplomatic preference, but an existential necessity.

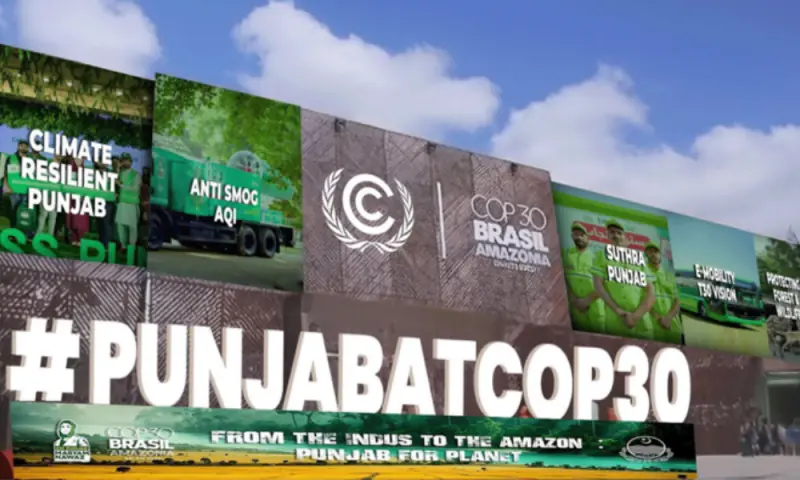

Header image: Pakistan’s Punjab pavilion at the COP30 conference in Belém, Brazil, on November 10, 2025 — photo by Marriyum Aurangzeb/X