ISLAMABAD: A Supreme Court judge on Saturday said that judges were not supposed to be influenced by appeasement or flattery, nor should they harbour malice or venom against any party while discharging their sacred duty of imparting justice in accordance with the law.

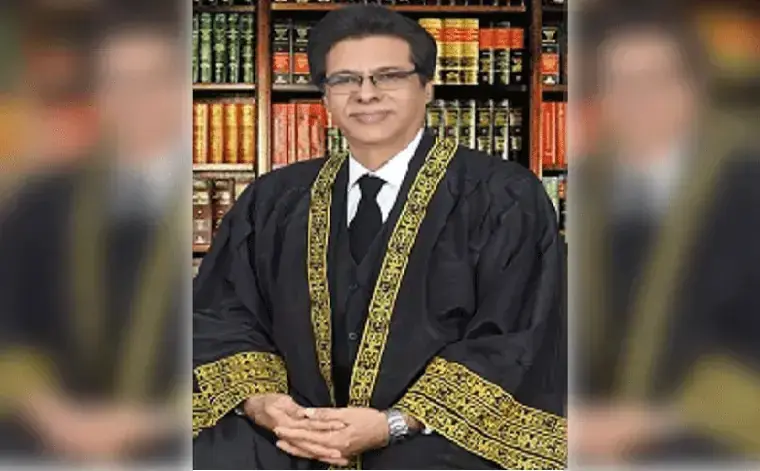

“The tolerance and forbearance of judges must not be so fragile or touchy as to make them easily annoyed during the hearing of a case, which is a sacred duty and trust,” observed Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar in his opinion rendered on the long-pending presidential reference seeking an answer to whether the court could revisit the 1979 judgement that sent former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto to the gallows — a verdict that the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP) and jurists regard as a historic wrong.

On March 6, 2024, after a delay of over 44 years, the SC finally corrected a historic wrong by accepting that the murder trial of former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto was unfair and lacked due process, both at the trial stage and in the endorsement of the verdict by the appellate court.

In his delayed opinion, Justice Muhammad Ali Mazhar, who was a member of the SC bench that heard the reference, emphasised that if a judge becomes annoyed with a litigant or their advocate in an unruly manner and loses patience, control or peace of mind, it becomes difficult to impart justice in accordance with the law.

In his opinion on Bhutto reference, judge observes admission by late Justice Shah leaves no doubt about ‘judicial murder’

He said judges should therefore remain calm, be good listeners and, instead of arguing themselves, which is the core function of lawyers, must allow counsel the opportunity to present their cases and arguments.

Justice Mazhar observed that in almost all cases where appeals are filed against the confirmation of the death penalty, no advocate directly seeks conversion of the sentence to life imprisonment. Instead, they strive for a fair acquittal for their client, which is the professional duty of every lawyer.

Simultaneously, the appellate court, with its sense of right and wrong, always has inherent jurisdiction to affirm, set aside or modify sentences. However, despite established bias and grave violations of natural justice and due process in the trial and conviction of Mr Bhutto, the punishment in this case was maintained.

The matter did not end there, the appellate court also missed the opportunity and failed to consider mitigating circumstances, despite overwhelming material on record that could have justified an acquittal or, at the very least, conversion of the death penalty to life imprisonment. This omission, Justice Mazhar said, was tragic, atrocious and reprehensible.

Referring to the delayed opinion, Justice Mazhar observed that although the SC rendered its opinion almost 13 years later, it could still be said that it was better late than never. “In my view, there is no plausible justification for the delay in deciding the presidential reference,” he regretted, adding that he was at a loss to understand why the reference was kept in cold storage and why the hearing was not commenced immediately after the questions were framed by the SC.

Referring to interviews of late Justice Nasim Hasan Shah at a belated stage, Justice Mazhar recalled how the former chief justice had admitted, in print and electronic media, that the decision on Mr Bhutto’s appeal was made under coercion.

This admission, he observed, left no doubt in the mind of a sane and prudent person that it was a “judicial murder”, and such an admission constituted a violation of his oath.

The disclosures made in those interviews, though belated, not only blew the whistle on the biases involved but also pierced the veil of the entire trial and conviction, exposing blatant violations of fair trial principles with the complicity of the judges who conducted the proceedings.

Justice Mazhar noted that the SC unanimously identified various lapses and biases and ultimately concluded that the trial conducted by the Lahore High Court and the subsequent appeal before the SC failed to meet the constitutional requirements of a fair trial and due process, as enshrined in Articles 4 and 9, and later guaranteed as a separate and independent fundamental right under Article 10A of the Constitution.

Published in Dawn, February 1st, 2026