CULTURE: FADING INTO SILENCE

The night the last full Heer was sung in a village in Jaranwala, the moon was so bright that old men swore Ranjha himself had returned to listen.

Three brothers — Ghulam Haider, Allah Ditta and Mohammad Bakhsh — all past 90, sat on a cracked mud platform beneath a single bulb. They began after maghrib [sunset] and finished only at the fajr azaan [call to prayer at dawn]. That night, they moved through the old qissay [tales] — Heer Ranjha, Mirza Sahiban and others — without missing a single couplet. Twelve unbroken hours, thousands of couplets, not one repeated. When Sahiban begged Mirza to shoot her first, even the village dogs fell silent. The youngest listener was 63. No child was present.

That was 2003. Today, the platform sells motorcycle parts, the bulb is gone and the brothers rest in the village graveyard.

A THOUSAND YEARS IN MEMORY

For a thousand years, the memory of Punjab lived in breath and melody rather than ink. From the salt hills of Soon Valley to the barley fields of Sargodha, every village once kept its history inside the heads and hearts of its mirasis [musicians], qissakhwaan and dastaangos [bards and storytellers].

Their stage was the dera [gathering place] or chaupaal [pavilion] under a peepal tree or outside the village mosque, where men gathered on charpais [woven jute beds] after evening prayer. In the parallel women’s spaces — the aangan [courtyard], the chhapparr [thatched hut], the rooftop terraces — grandmothers ruled the night with the same authority as queens.

For a thousand years, Punjab kept its history in song, not script. Now, fewer than a dozen people can still perform the epic tales that once filled every village square. This is the story of what we’re losing, and the unexpected voices trying to save it…

The great lok dastaans [folk tales] were the pillars of this living library: Heer Ranjha (dozens of oral versions long before Waris Shah put pen to paper), Sassi Punnu (originally a Sindhi and Balochi legend, later adapted to Punjabi oral tradition), Mirza Sahiban, Sohni Mahiwal, Puran Bhagat, Dulla Bhatti, Kaulan Rasalu and countless local heroes. Around them circled shorter stories, Bulleh Shah’s kafiyaan [spiritual poetry], seasonal barah-maha [twelve months] songs, wedding sohile [emotional songs for bride] and the long shajras [genealogy] recited at every nikaah to trace a family back to its saint or tribe.

Women kept their own parallel epics alive. In the Seraiki belt, only a handful of elderly women in remote villages of Bahawalpur and Rahim Yar Khan still remember the complete cycle of suhaag and ghorriyaan [traditional Punjabi wedding folk songs] that used to accompany a bride from her parents’ home to her in-laws’ over seven nights.

In Potohar and the Salt Range, the sharp-tongued mahiye and tappay [fast-paced celebratory songs] once traded between rival clans at weddings have almost vanished; the last full-performance recording Lok Virsa — the National Institute of Folk and Traditional Heritage — managed was in 1998.

THE LAST VOICES

Two living legends still carry the male tradition, though both know the fire is low.

In Mochiwala near Multan, Ustad Fazal Abbas (born 1946), from a hereditary mirasi lineage, is the last man in southern Punjab who can perform the complete 48-hour Dulla Bhatti — about a Punjabi Robin Hood who rebelled against Emperor Akbar — without a written line. His voice, roughened by decades of hookah and winter nights, still fills the small dera beside the village shrine every Thursday.

In 2023, he began teaching his two teenage grandsons, but they leave for factory jobs in Faisalabad every Sunday morning.

Seven hours north, in Adda Jahan Khan near Bhakkar, Ustad Sharif Ahmed Qissakhwaan (born 1942) keeps alive the 36-hour oral cycle of Raja Rasalu, another folktale. Every spring, on the urs [death anniversary] of a local saint, he sits beneath an ancient ber [jujube] tree and sings from sunset to sunrise. Farmers still bring him food, but the audience rarely exceeds 30 people, and most are over 50.

“The young ones record me on their phones,” he says with a tired smile, “but they do not learn with their hearts.”

These two men are among fewer than a dozen traditional performers still left in the province (Lok Virsa internal survey, 2022). In Punjab’s villages, electricity arrived in the 1980s, television in the 1990s, smartphones after 2010. Farm debt and city jobs pulled young men away.

Centuries-old caste prejudice, which labels hereditary musicians as of “low” social standing, now pushes their descendants to take up welding or driving instead. The pandemic years of 2020–2022 cancelled weddings and festivals; many elders died without apprentices at their side.

IMPERFECT RESURRECTIONS

Yet sometimes, in the middle of our loud, forgetful cities, the desert still speaks.

A young Urdu literature professor and poet, who signs his name “Imran Feroze”, has written a Sassi that no village grandmother ever sang, yet every line feels older than Bhambore itself. He gives voice to Sassi after she has become sand and memory, after her body is gone, after even her grief has turned into dunes. Here is a fragment of what she says to Punnu from the other side of death:

[What is the point of returning now Punal?

Love has been buried in the khanzada’s harem now

Now a shroud of dust covers every dream of mine

Punal, do not call out…

For every voice is a wound.

Punal, turn back and go

Here nothing remains except the

blood-soaked sand]

When I first read those lines, I heard the same ache I hear in Ustad Fazal Abbas’ cracked voice. The tradition is not only dying, it is also — against all odds — being reborn in new throats that never sat on a charpai under a peepal tree.

That is the other half of the story we rarely tell: that a few young people are still trying, however imperfectly. In a government girls’ school in Faisalabad, Ayesha Parveen keeps 20 students after the bell, teaching them fragments of Sohni Mahiwal in Seraiki. The girls love it — until parents arrive, complaining that the time would be better spent prepping for college entrance tests.

In a narrow lane of Lahore, 24-year-old Hamza Ali once recorded a three-minute Heer on his phone, added beats and played it for cousins. The elders called it disrespectful, so he deleted it the same night. Now, every Friday, he sits with his grandfather, recording the old man’s raw, unfiltered Mirza Sahiban and sends the clips to a group of friends with the same plea: “This is the real thing. Listen before it’s gone.”

PROTECTING A VANISHING ART

Saving what remains is still possible, but the clock is brutal. The Punjab government once paid a modest Rs8,000 monthly stipend to recognised folk artists; the scheme quietly died in 2018. Reviving and raising the stipend to at least Rs40,000, tied to compulsory teaching of two apprentices — as has been proposed by the Punjab government — would cost less than one kilometre of the metro bus track and secure more living heritage than any museum.

Lok Virsa’s thousands of reel-to-reel hours remain largely undigitised; a proper, publicly accessible Shahmukhi [Punjabi script] archive with melody, dialect notes and performer genealogies is long overdue.

Even the language is flattening. The rich, rolling Multani of Sassi’s desert and the hard consonants of Potohari Rasalu are being replaced by textbook Urdu or the clipped Punjabi of short-form video. In schools, children study eight couplets of Waris Shah’s Heer in grade 10, never told that the full oral versions once ran to 6,000, changing with every teller, every season, every heartbreak in the audience.

Until serious steps are taken, two old men — one in Mochiwala and the other in Adda Jahan Khan — will keep singing to a shrinking circle, beneath the same moon that once listened to Ranjha. And somewhere in a Lahore flat, a young poet will write lines that taste of sand and eternal waiting.

When all the old voices finally stop, the rivers will still flow, the peepal trees will still stand, but maybe, just maybe, a Punjab older than writing will still find new tongues willing to remember its songs.

The writer is Senior Project Manager at the Citizens Archive of Pakistan. He can be contacted at salmanhistorian@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 14th, 2025

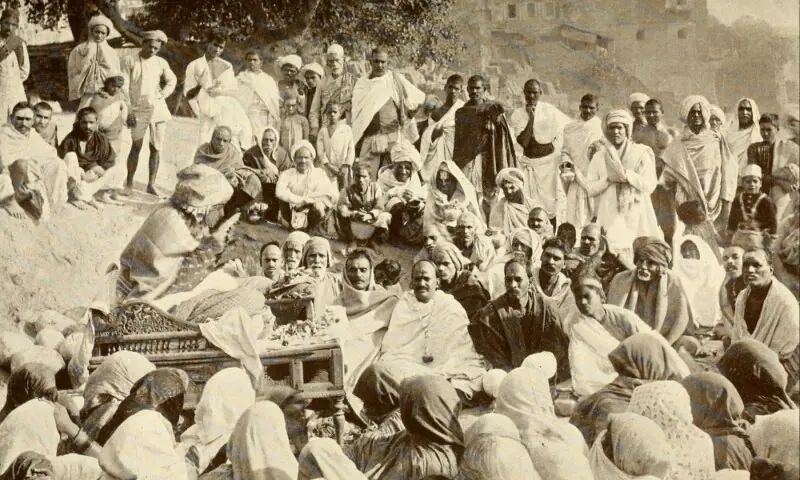

Header Image: A village storyteller, circa 1913 | Wikimedia Commons