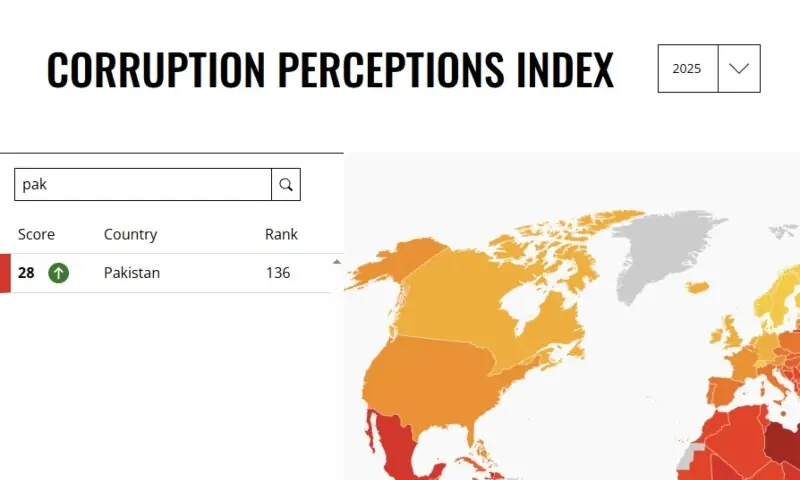

Pakistan’s ranking in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) 2025 improved by one point, moving from 135 out of 180 countries in 2024 to 136 out of 182 countries in 2025.

At the same time, the country’s CPI score increased by one point, from 27 in 2024 to 28 in 2025, according to Transparency International’s report published on Tuesday.

While Pakistan is undertaking commendable efforts in governance and institutional reforms, it is imperative that the recommendations of the IMF Governance and Corruption Diagnostic Assessment are implemented effectively. This is essential to sustain Pakistan’s upward momentum in the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) in the coming years, says the Chair of Transparency International Pakistan, Justice Zia Perwez.

The Berlin-based Transparency International (TI) notes that corruption is worsening globally, with even established democracies experiencing rising corruption amid a decline in leadership.

The 2025 index shows that the number of countries scoring above 80 has shrunk from 12 a decade ago to just five this year.

The score has changed since 2012: 31 countries improved, 50 countries declined, while 100 countries stayed the same.

This year’s CPI ranks 182 countries and territories according to the levels of public-sector corruption perceived by experts and business people.

Chair of Transparency International, Francois Velerian, said: “Corruption is not inevitable. Our research and experience as a global movement fighting corruption show there is a clear blueprint for how to hold power to account for the common good, from democratic processes and independent oversight to a free and open civil society.”

“At a time when we’re seeing a dangerous disregard for international norms from some states, we’re calling on governments and leaders to act with integrity and live up to their responsibilities to provide a better future for people around the world.”

The highest-ranked nation was Denmark, for the eighth time in a row, with a score of 89. Only a small group of 15 countries, mainly in Western Europe and the Asia-Pacific, managed to get scores above 75. Of these, just five reached scores above 80.

Meanwhile, over two-thirds of countries (68 per cent) fell below 50, indicating serious corruption problems in most parts of the planet.

At the bottom of the index, the countries scoring below 25 are mostly conflict-affected and highly repressive countries, such as Venezuela, and the lowest scorers, Somalia and South Sudan, which both scored nine.

Data show that democracies, typically stronger on anti-corruption than autocracies or flawed democracies, are experiencing a worrying decline in performance. This trend spans countries such as the United States (64), Canada (75) and New Zealand (81), to various parts of Europe, such as the United Kingdom (70), France (66) and Sweden (80).

Another concerning pattern is increasing restrictions by many states on freedoms of expression, association and assembly. Since 2012, 36 of the 50 countries with significant declines in CPI scores have also experienced a reduction in civic space, TI says.

The CPI shows the stark contrast in controlling corruption between nations with strong, independent institutions, free and fair elections, and open civic space, and those ruled by repressive authoritarian regimes.

Full democracies have a CPI average of 71, while flawed democracies average 47 and authoritarian regimes just 32. Although a very small number of non-democratic countries score relatively well compared to their regional peers, and are perceived as managing a limited range of corruption types successfully, they remain exceptions.

Similarly, countries where civic space is guaranteed and protected tend to control corruption better. Those where the freedoms of expression, assembly and association are duly safeguarded are generally more resilient against corruption and score better on the CPI.

However, countries where these freedoms are lacking are more likely to lose control of corruption: 36 of the 50 countries where the CPI scores have significantly declined have also seen a reduction in civic space.

TI is calling on governments and leaders across the world to take action to strengthen justice systems, ensure independent oversight of decision-making and public spending, guarantee transparency about how political parties and election campaigns are funded, and protect civic space, democracy and media freedom.

This year, governments that fail to address their citizens’ concerns may find themselves toppled by popular protest movements. By choosing to act for the public interest, not private gain, governments and leaders can live up to their responsibilities to shape and nurture safe, fair and healthy societies where everyone can thrive, TI says.

TI CEO Maira Martini commented that at a time of climate crisis, instability and polarisation, “the world needs accountable leaders and independent institutions to protect the public interest more than ever – yet, too often, they are falling short.”

Some powerful nations have an indirect impact on corruption levels that extends well beyond their borders.

The Russian state has been accused of interfering in other countries’ elections by spreading disinformation and buying votes with the intention of influencing voters and driving instability, democratic backsliding and the narrowing of civic space.

The US government’s decision to temporarily freeze and then degrade enforcement of its Foreign Corrupt Practices Act – a key anti-corruption law that prohibits corporate bribery of foreign officials – sends a dangerous signal that bribery and other corrupt practices are acceptable.

At the same time, US aid cuts to funding for overseas civil society groups that scrutinise their governments have undermined anti-corruption efforts around the world. Political leaders in various countries have also taken this as a cue to further target and restrict independent voices, such as NGOs and journalists.

The report recommended that, in order to function properly, deter potential offenders and protect people who speak out against corruption, countries’ justice systems must be shielded from interference by political or economic interests.

This includes protecting appointments and promotions from external pressure. These systems also need to be properly resourced, prosecutorial decisions must be reasoned and reviewable, and courts should publish decisions and data.

Fundamental freedoms – including a free press and the right to information – enable the active engagement of individuals and groups to promote transparency and integrity in government and business activities. Decision-makers must fully protect civil society groups and people reporting corruption, such as whistle-blowers.

They should also create a regulatory framework that enables, rather than restricts, the work of civil society organisations – including giving them access to both domestic and international funding. This will strengthen the fight against corruption by allowing civic actors to expose abuse, assist victims, foster public participation and build accountability.

When journalists are attacked or killed for investigating corruption, power cannot be held to account effectively and corruption tends to worsen.

Since 2012, in non-conflict zones worldwide, 829 journalists have been murdered. 150 were killed while covering corruption-related stories, five of them in 2025. Over 90 per cent of these killings happened in countries with a CPI score lower than 50, including Brazil, India, Mexico, Pakistan and Iraq, which are particularly dangerous for journalists reporting on corruption.

Citizens deserve to know who funds political parties and candidates, or who influences decisions. It is important that political finance, conflicts of interest and lobbying are regulated, documented and subject to public scrutiny to ensure that democracy is protected against potential corruption.

Transparency and limits on political donations stop rich and well-connected industry groups from being able to unfairly influence policies, budgets and public institutions to suit their own goals, rather than the public interest.

The report recommended that robust checks and balances at home, together with strong national and international prevention and detection measures, are essential to block and uncover large-scale, high-level corruption and major cross-border money laundering.To deter and punish these serious crimes, more effective enforcement systems are essential.

Overcoming pervasive and deep-rooted state corruption will require strong national coalitions to rebuild democracy and the rule of law. International enforcement in states with effective justice systems can also play a vital role by prosecuting wrongdoers and seizing stolen assets hidden abroad, to cut off their ability to operate.