Basant, also known as Jashn-i-Baharaan, has for centuries marked the arrival of spring in Punjab, announcing the end of winter’s restraint and the beginning of warmth, colour, and movement. Rooted in the ancient idea of Vasant — spring as both a natural and emotional rebirth — the festival gradually evolved from a seasonal observance into a deeply textured cultural practice. Traditionally celebrated around the fifth day of Magh, Basant was never confined to a single ritual. It unfolded as a collective mood: yellow garments echoing mustard fields, rooftops alive with kites, kitchens fragrant with seasonal foods, and streets humming with anticipation. In this sense, Basant belonged less to the calendar and more to the psyche of the region.

In pre-modern Punjab, whether rural or urban, spring was not merely observed but welcomed. The colour yellow symbolised both agricultural abundance and the strengthening sun, while the act of kite flying transformed the sky into a shared canvas. The festival gained particular prominence in the 19th century under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, who formalised Basant celebrations at the Sikh court. Dressed in yellow, flying kites from palace rooftops, the ruler turned a folk tradition into an imperial spectacle without stripping it of its popular character. Cities like Lahore, Amritsar, and Kasur became synonymous with Basant, their skies thick with competing kites, their rooftops echoing with laughter, music, and calls of triumph. Yet even as the celebration acquired royal patronage, it remained rooted in the everyday life of the people.

Nowhere did Basant take on a more distinctive urban character than in Lahore. Over time, it became part of the city’s annual rhythm, a moment when social boundaries softened and neighbourhoods opened themselves to one another. Rooftops ceased to be private enclosures and turned into shared platforms of festivity. Kite makers, string dyers, musicians, food vendors, and artisans found their livelihoods intertwined with the season. The city, for a few days, seemed to breathe differently.

Cultural historian Nazir Ahmad Chaudhary, in his work Basant: A Cultural Festival of Lahore, captures this essence with striking clarity. In one passage, he observes, in translation:

“Basant was not merely the act of flying kites; it was the moment when Lahore lifted its head towards the sky. For a few days, the city forgot its divisions — rooftops became shared spaces, strangers exchanged greetings, and even silence felt festive. In those yellow mornings, Lahore revealed its true temperament: playful, generous, and incurably alive.”

Elsewhere, reflecting on the festival’s inclusive nature, he writes:

“No one asked who believed in what. The kite did not inquire whether the hand that released it was Muslim, Hindu, or Sikh. Basant belonged to the season — and the season belonged to everyone.”

For Chaudhary, Basant was a form of urban civility, a lived culture rather than a religious rite, an expression of how a city learned to live with itself.

This sensibility is echoed, though in a more intimate and elegiac tone, in the writings of A. Hameed. In his essays on Lahore, especially in Lahore Ki Yaadein, Basant appears as a repository of memory and feeling. He recalls the city during Basant as if it were a living being momentarily freed from the weight of time. In translation, he writes:

“In Basant, Lahore behaved like a child who has been promised a fair. Even the old forgot their age, and the poor forgot their troubles — if only for a day. The sky became a page on which the city wrote its happiness in colour.”

When the festival disappeared from public life, A. Hameed sensed a deeper loss:

“When Basant vanished, something else vanished with it — the courage to be openly joyful. A city that stops celebrating the seasons slowly stops recognising itself.”

His writing suggests that festivals like Basant function as emotional infrastructure, sustaining a city’s humanity as much as its roads and buildings sustain its movement.

Beyond memory and social practice, Basant has long occupied a rich space in the poetic and mystical imagination of South Asia. The association of spring with renewal, love, and awakening made it a natural metaphor for poets and Sufis alike. Amir Khusrau, the 13th-century poet and musician, is perhaps the most iconic figure linked with Basant’s poetic spirit. Legend recounts that upon witnessing Basant celebrations — women adorned in yellow, fields blooming with mustard — Khusrau dressed in yellow himself and composed verses celebrating the season. In a sense-translation attributed to his Basant compositions, he exclaims:

“Sakhi, Basant has arrived — the earth wears yellow, the sky leans closer, and even sorrow loosens its grip.”

In Khusrau’s work, spring is both literal and metaphysical: the blossoming of the earth mirrors the awakening of the soul, and joy becomes a pathway to the divine.

Punjabi Sufi poetry continued this tradition, using Basant as a symbol of inner transformation. Shah Hussain, in his kaafis, draws a direct parallel between the fields and the heart, reminding the listener:

“When Basant blooms in the fields,

let it bloom in the heart as well.”

The message is clear: external change is incomplete without internal renewal. Even poets like Bulleh Shah, who did not write explicitly about Basant, resonate deeply with its symbolism through their recurring imagery of colour, movement, and freedom. “Let me be dyed in the colour of love,” he implores, “yellow, red, or any that frees me.” In modern times, Faiz Ahmed Faiz reimagined spring as a metaphor for hope and resistance. His call to “bring colour back to the gardens — even if the season resists” echoes Basant’s enduring promise that renewal is possible, even under constraint.

Historically, Basant thrived in a pluralistic social landscape. Pre-Partition Punjab was home to Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, and others who participated in the festival together, often without conscious reflection on religious difference. While Basant Panchami held religious meaning for some, the Punjabi expression of Basant became broadly secular, grounded in nature rather than doctrine. It exemplified what is often described as the Ganga-Jamuni ethos — a syncretic culture shaped by shared language, music, food and seasonal rituals. The festival’s eventual suppression in the early 2000s, through a blanket ban on kite flying, disrupted not only a practice but a collective memory. For many Lahoris, it felt as though a vital thread connecting past and present had been severed.

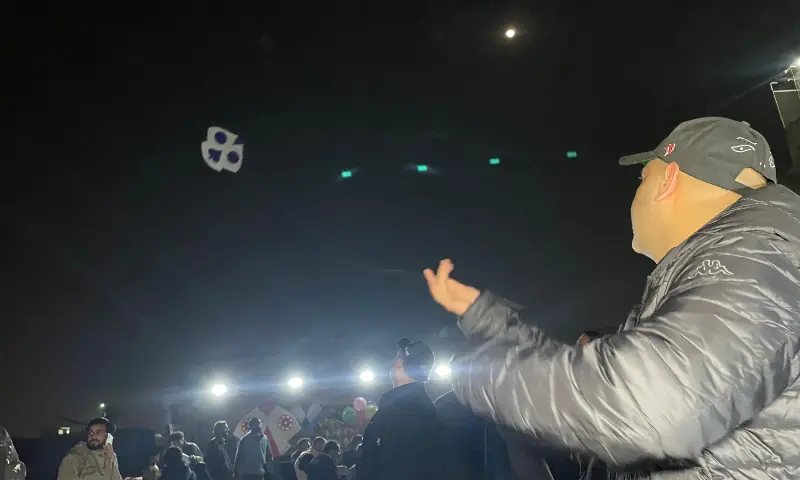

The recent revival of Basant under regulated conditions has, therefore, been greeted with cautious optimism. It is seen not simply as the return of kites to the sky, but as the re-entry of colour, rhythm, and communal joy into the city’s public life. Contemporary writers have aptly described Basant as “the last festival that did not ask for identity cards”, “a rehearsal for coexistence”, and “a sky large enough for everyone’s dreams”. Such descriptions underline the festival’s symbolic weight in an age marked by fragmentation and anxiety.

Ultimately, Basant endures because it speaks to something elemental: the human need to celebrate change, to mark time not only through hardship but through joy. From the poetic imagination of Amir Khusrau to the cultural histories of Nazir Ahmad Chaudhary, from the tender nostalgia of A. Hameed to the lived memories of generations of Lahoris, Basant emerges as a living archive of shared heritage. It reminds us that cultures remain vibrant not through preservation alone, but through participation. In a world increasingly suspicious of collective pleasure, Basant offers a quiet yet powerful lesson — that to celebrate the seasons together is also to reaffirm faith in one another.

Published in Dawn, February 6th, 2026