Death has a way of rearranging the furniture of life. Drawers that have remained shut are opened and stories whose memory has grown faint re-emerge with greater clarity. If you’re lucky, you’ll find something insightful in what’s been left behind by the dearly departed. And, on the rare occasion, you may just find something revelatory.

You may just find a bundle of 159 letters tied together with a string, charting one man and his family’s extraordinary circumstances from 1971 to 1974.

This is that man, and that family’s, story.

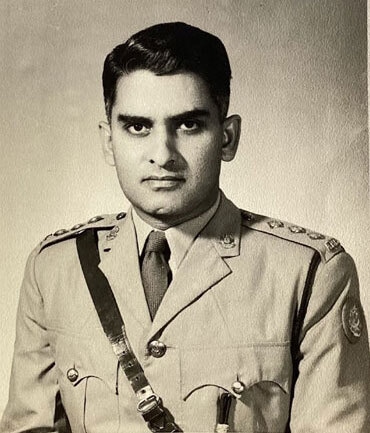

The 159 letters written by my Nana [maternal grandfather], Saiyid Safdar Nawab, emerge a few days after his passing on December 26, 2025. They tell a story that spans the length and breadth of the Subcontinent, much like the fortunes of my family itself.

But, as with most stories, we’ll have to start at the beginning.

From 1971 to 1974, Saiyid Safdar Nawab wrote more than 150 letters to his family in Pakistan while he was held in India as a prisoner of war (POW) after the 1971 Indo-Pak war. The letters, discovered upon his death in December, present a poignant portrait of what it was like to live in POW camps for three years, separated from his family and his life back home, and the agonising wait for a return…

Born in Aligarh in 1932 to a father who was a sessions court judge, Safdar Nawab migrated to West Pakistan at the age of 20. After completing his postgraduate studies in physics, he joined the Army Education Corps (AEC) in May 1957 and taught at the Pakistan Military Academy (PMA) for more than 10 years.

In 1971, following the closure of the MT (military training) Directorate at the General Heaquarters (GHQ) in Rawalpindi, he was asked to join the Martial Law Headquarters in Dhaka as a G-2 (an information collection and analysis role). The officer initially chosen for the task wiggled his way out of the job and so, through a strange twist of fate, Safdar Nawab landed in Dhaka (or, as he spells it in adherence to its colonial-era spelling, “Dacca”) in August 1971. His wife and two children stayed back at their home on Hythe Road in Rawalpindi.

By this point, tensions were already high as Pakistan’s military action in East Pakistan had begun on March 25, 1971 — and things were only set to escalate even further once the Indian army marched into East Pakistan a few months later. After the Indo-Pak war in December of that year, the Pakistan military personnel stationed in Pakistan’s former Eastern wing became prisoners of war (POWs).

It is in the immediate aftermath of the war that Safdar Nawab sent his first letter from this collection of 159.

IN ‘DACCA’

Written on December 27, 1971, it is addressed to his wife, Shahnaz Nawab, his son, Syed Raza Nawab (aged 11), and his daughter, Mahnaz Nawab (aged two). It is written on an International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) message form, which has instructions on it in English, Urdu and Bengali. A stamp on the paper states, “Prisoner of War Mail”, while an instruction declares “Not over 25 words, family news of strictly personal character only.” The details mentioned on the form are as follows:

Sender: Major SS Nawab AEC

Postal Address: HQ MLA Sector 5 ZONE B CAMP B c/o ABPO-99 Dacca Cantt

Country: East Pakistan

Receiver: Mrs Shahnaz Nawab

Postal Address: 4-A, Hythe Road, Rawalpindi Cantt, West Pakistan

The message reads: “I wish and pray that you are well. I am fine and hope to see you all soon. We move out of Dacca in two weeks’ time.”

But, as the stamped date in the corner reveals, this message form doesn’t reach the Rawalpindi General Post Office (GPO) till February 21, 1972. In fact, the more than dozen letters that he writes over the course of those initial four months after the war are written without him even knowing whether his words are reaching his family.

Nevertheless, he keeps writing.

From giving personal updates in early January, such as “I am still in Dacca and quite comfortable. Our messing arrangements are excellent. Most of the time we spend working for the welfare of our men. I am in perfect health”, to trying to give reassurances during an uncertain time — “I am not sure if you have read my letters. I have been writing frequently. We may move out tomorrow. Shall write on reaching the next station with my address. Don’t write back for the time being. I am fine and fit. Have no worries about me. Look after yourself and pray for an early reunion” — he keeps writing.

For those few months after the war, while he keeps sending his posts, his loved ones back home have no knowledge of his whereabouts or his well-being.

However, after January 16, 1972, Safdar Nawab doesn’t write a letter for another 10 days. The reason why becomes apparent in what he sends next.

TRAIN TO INDIA

When he writes again, it is on a plain-looking postcard sent on January 26, 1972, but now the instructions on it are in English and Hindi. “Prisoner of War Mail” remains emblazoned in the corner and now his details read as follows:

Name: Major Safdar Nawab

Place and date of birth: Aligarh, 1.7.32

Prisoner of War No. S-4684

Name of camp: No 33 c/o APO 56

Country where posted: India

He is now a POW in the land of his birth.

While the Rawalpindi mailing address on the card stays the same, the country the card is being sent to is referred to as “West Pakistan.” This is the last time it will be referred to by this name in these exchanges.

Safdar Nawab says: “I am sorry I could not write for over 10 days. We left Dacca on the 17th and arrived here near Roorkee on the 24th. It was a long but interesting and comfortable journey… I am keeping fine health and hope that you all are also well. Please look after yourselves. Tomorrow is Eid — Eid Mubarak to all of you.”

His journey from Dhaka into the hinterland of India was indeed “interesting” as he passed through Uttar Pradesh (UP) and lands he was all too familiar with during his youth.

This message also betrays a glimpse of the watchful eye that the Indian army must keep on these cards, letters, notes sent by POWs as the words “near Roorkee” have been slashed out, but its mention shall surface in later letters. The majority of these 159 missives are written in English, with some longer, more detailed ones in Urdu scattered in between.

His stay here in Roorkee proves to be only temporary, as he reveals in his next letter, sent on February 11, 1972. The country of mailing is now simply referred to as “Pakistan” and Safdar Nawab pens: “Last week we have moved from Camp 33 to Camp 54. It is in Central India. We have good company with us. Noor [ul Haq] and Zuberi are also here.”

But there are no letters arriving for him from Pakistan, and it seems this absence is gnawing at him as much as the captivity itself. After it seems like the Indian POW postcards are not reaching his family, Safdar Nawab writes a letter on a page from a notepad and places it in an envelope that has a green Pakistani postage stamp on it that proudly displays the country’s name in Urdu, English and Bengali like a remnant from a fractured dream. The envelope has been stamped by the ICRC Islamabad. The contents of this letter sent on March 6, 1972 addressed to Shahnaz Nawab read as follows:

“For the last three-and-a-half months, I haven’t heard anything. We don’t understand why the mail hasn’t reached us. I only wish you are getting my letters”, and “I have been writing very regularly to you. Since December last year, I haven’t received any letter from you… We left Dacca on January 17, reached Roorkee on the 24th. On February 7th we came to this camp, which is near Sagar in CP [Central Province]. Life over here is very drab… I hope that we will soon meet… I am confident you will stand with courage… I am anxious to know about your welfare.”

It is also evident in several of the letters sent across March 1972 that Safdar Nawab is trying to assuage and allay what he perceives will be his family’s fears regarding news of trouble in some of the POW camps in India: “You might have heard some news about one of the camps in India. It is all well with us… We are all safe in this camp… There is nothing to do for us [here] and we spend the days quietly in our quarters.”

He spends all of April 1972 without receiving a single word from his family and without knowing if they have any information of his present situation.

And then, finally, a breakthrough.

LIFE IN CAMP 54

The excitement is palpable in the message he writes on May 2, 1972: “Received your [Shahnaz Nawab’s] three letters just now. The latest one, on this address, is dated April 1, 1972. The other two letters are addressed to Camp 33, dated March 1 and March 4. I felt much relieved on receiving these message forms after a gap of four-and-a-half months.”

Now that the channel of communication has been established, husband and wife begin exchanging updates with one another as, from inside Camp 54, Safdar Nawab continues to plan a future. He writes about potentially having a house built in Rawalpindi, whether the finances are being managed alright, his children’s schooling and how the rest of the wider family is doing. They both tell each other to not worry.

If anything, the knowledge of what is happening back home offers him an escape from the “monotonous life” in Camp 54. He offers us a window into what day-to-day life would have been like in those POW camps and, on May 6, 1972, he notes:

“Food arrangements over here are satisfactory. We are five of us in a neat little house. Running water with electricity is available. Overall, it is not bad. There is good company of our officers around and we are quite comfortable… There is enough time for prayers. Playing bridge is another pass-time [sic]. We are also getting Rs 110 per month as an allowance, which is mostly spent on eatables. Eggs, jams, fruits, fish, butter, achaar, milk, Ovaltine, squash etc are available in the canteen. There are books to read as well.”

He continues: “Yesterday each of us received one Pakistani packet containing towels, socks, biscuits, toothpaste, sleeping suit, chappal, PT shoes etc etc, in all 19 articles. Though we didn’t need all that, it was most welcome. Everybody felt extremely delighted and proud. You may please convey thanks to the authorities in Pakistan responsible for the gifts. This was from the Ministry of Defence through the Pak Red Cross. The morale of our men over here is high. None of us would like our government to bargain at our cost. We are ready for all sacrifices for the sake of our country… Inshallah, we will return soon, but with honour.”

But while his letters continue to state that his living conditions are satisfactory, it is evident that the concern for his wife and children in Rawalpindi is perhaps taking more of a toll on him than his own situation: “Your letters have given me great strength and have helped me in keeping my morale up. However, I often feel that you must have undergone the greatest test and mental agony during the last one year… I wish I could do something more to console you than just writing letters.”

On August 5, 1972 he writes, “It has now been over a year since I left Pindi”, and that sense of melancholy seeps through in his letter on August 10, 1972: “In your latest letter, you have said that she [Mahnaz Nawab] is speaking many sentences now. This is the most interesting age for her… I shall ever miss this period of her life.”

He is meticulous about keeping track of the letters and the dates on which he has received or sent them, and the information he has conveyed in them. His letters detail how Ramazan, Eid and Muharram are all observed in the camp. How “volleyball and cricket matches [are held] amongst 300 officers in the camp”, and how he buys “Illustrated Weekly of India and Daily Times of India regularly”, listens to the “transistor radio” and is “collecting the pages of Dennis the Menace cartoons” for his son.

A few letters are written in delight after receiving parcels sent by his wife “containing one nylon shirt, one pyjama, one jersey, one vest and one pair of socks” and “four biscuit packets, two BP toffee packets, two packets of fruit drops, two special British toffees and a big chocolate packet.” He also reminds his wife: “Probably I had written to you earlier that I am carrying all my personal belongings with me which I had at Dacca.”

While he tells Shahnaz Nawab not to worry herself by sending several parcels, the one and only thing he repeatedly keeps asking for her to send him is a picture of what his family looks like now. The delays in his letters reaching her, and in her letters reaching him, means that several months pass by without this desire being fulfilled.

And then, on April 28, 1973, the greatly-anticipated photograph finally arrives: “Received your detailed letter of March 15… and, above all, the most-awaited letter of March 1, enclosing the photograph. The photograph is lovely and I liked it very much. Though it took two months to reach me, but it gave me enormous pleasure.”

He looks at his children in the photograph. He does not know when he’ll be able to meet them again.

‘BRING THEM HOME’

Safdar Nawab, in his letters from 1971 to 1974, is convinced that, sooner or later, he will return home. His hope cannot be dimmed.

In June 1972, he writes that he is “praying for a reunion next month.” This optimism is spurred by what he notes in his message form on June 28, 1972: “President [Zulfikar Ali] Bhutto has arrived in Simla today. Let us hope some understanding and settlement is arrived at. The chances of our return are a bit brighter.”

After the summit, he writes on July 4, 1972: “The summit is over. Under the circumstances, it is the best bargain… In a couple of months’ time we hope the repatriations will also be completed.”

On December 1, 1972 Safdar Nawab writes about a significant development: “The POWs in Pakistan have been released. We have all appreciated the gesture by our president. Hope we will also return soon.” And on December 8, 1972 he notes, “Only yesterday, the decision regarding the withdrawal of troops from the border has been arrived at. Once the troops withdraw, something may follow for us. It appears that it may take us some time more before we return — maybe March/April 1973.”

With an eye on the evolving diplomatic situation, he writes on April 10, 1973: “During the last 10 days, since [P.N.] Haksar went to Dacca, it appears that the stalemate is likely to break. It looks that in the near future there will be some good news about our return to Pakistan. By the time you get this letter, something definitive might emerge.”

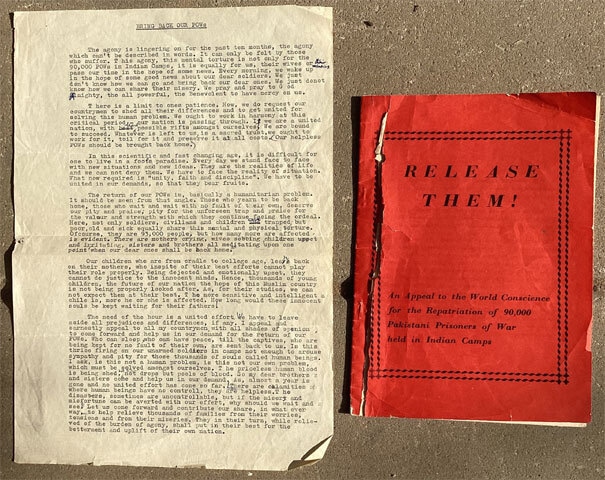

While Safdar Nawab reads the newspapers and listens to the radio to try and get a sense of when the repatriation process may start, his wife is already using her voice to advocate for it. Given her degree in English Literature and background in journalism, Shahnaz Nawab writes articles for several publications and pamphlets calling for the POWs to be freed.

When the United Nations Secretary General Kurt Waldheim lands in Rawalpindi in 1973, Shahnaz Nawab (with her daughter in her arms and her son by her side) and many other wives of POWs protest at the airport, demanding Waldheim take action to bring the Pakistani POWs back home.

The pressure will soon start to pay off. It has to.

FREEDOM IN SIGHT?

In the second half of 1973, the repatriation efforts begin to pick up steam. On August 29, 1973, Safdar Nawab observes, “The Indo-Pak talks in Delhi [later known as the Delhi Agreement] have been declared successful. The details are yet to be announced, but the indications are that most of the prisoners of war would be returning home. It is unfortunate that some of our brave soldiers will be further detained in India for more bargaining and exploitation. We hope and pray that the remaining POWs will also return to their families by the end of the year.”

Regarding his return, he explains in his letters in September: “With the latest developments and news, it is certain that our return is not far off. The Bengalis and Pakistanis have started moving and the first two trainloads of POWs from India will reach Lahore on the 28th and 29th of this month. With time, the transport and facilities for movement will increase and the flow of traffic will rise. It looks like most of us will be back between October 15 and November 15.

“It is understood that we will be detained in Lahore for two to three days before going on two months’ leave with the families… In case you get this letter before my return, please do not come to Lahore to receive me since the date will not be very definite and there will be too much of rush [sic] and you will find it too much of an inconvenience.”

With anticipation of his return building, he writes on September 28, 1973: “Today, the repatriation will start at Wagah. We hope that, in due course, the rate will increase and we should be back in a month or two.”

By October 12, 1973, he can see that the process is now underway: “Currently, POWs from Agra and Meerut are returning. Their first train will be reaching tomorrow. The names of those returning is announced on Radio Pakistan on the evening a train arrives. Our camp is near the city of Sagar, also known as Dhana. Here, along with our camp, there are five more camps, with nearly 1,000 people.”

But, in November, the process slows down: “This process is moving slower than I had expected. Another two three months, I hope… Once the UP camps are emptied, that is when our turn will come,” he writes. And in December: “Temporarily, the process of repatriation has stopped due to railway employees’ strike in India. Hope it will soon restart and all the backlog cleared.”

That wait will continue for an agonising amount of time because, on January 18, 1974, Safdar Nawab scribbles a message in the margins shortly before dispatching this letter: “Next four trains from this camp running this month have been announced. I am not leaving this month. See you next month, Inshallah.”

But his worries are about to be unexpectedly compounded. In his letter on February 25, 1974, he makes a revelation: “I am sending this letter through Captain Mehboob [Ahmed] who is departing today. We are not allowed to send letters with anyone leaving but because Captain Mehboob is at the hospital [with me] and is leaving for the train from here I’m hoping no one will stop this letter.

“Yesterday, I got admitted to the CMH [Combined Military Hospital] here. There is nothing to worry about, it’s just the back pain I wrote to you about. When I walk around too much it gets amplified. According to the Indian surgical specialist, there is nothing wrong with the bones and it will all soon be well on my return to Pakistan. The pain is said to be muscular, aggravated by poor diet and mental worries.

“Today the train that departs will be carrying 30 officers…[In] total, till tomorrow, eight trains would have departed from here… Now, nearly 170 officers are left [from our camp]. Nearly 115 officers have been sent home. Hoping the next few trains will be able to accommodate the remaining officers. Next train leaves February 28 and then March 10… They haven’t announced the names for the next train yet. I am praying to God that my name is on it and I can return home by March.”

His final letter out of these 159 is written on March 15, 1974 and says, “I am trying to send this letter to you through someone leaving by the train on March 16. There are two more trains to leave this camp in this month, reaching Lahore on March 25 and 29. The names of officers have not been announced yet.”

He is not going to be on either one of those trains.

THE FINAL JOURNEY

He was on the last train to leave “Dacca” for India. Now, Safdar Nawab is on the last POW train to leave India for Pakistan. From Sagar, he travels to Amritsar by train and then boards a bus to Wagah. He crosses over into Lahore on April 21, 1974. Shahnaz Nawab will forever remember this date, especially since it coincides with Allama Iqbal’s death anniversary. Safdar Nawab’s wife and son are there to receive him.

On his second day in Lahore, Safdar Nawab heads to the CMH to see the neurosurgeon on his own accord. The doctor tells him to just get some rest. He is told that his full medical check-up will be done in Kharian after two to three months.

By the end of 1974, he was promoted to Lt Colonel and, in November 1977, he was made a full colonel and appointed as the principal of Lawrence College in Murree. He retired as a brigadier and went on to work at the Dr A.Q. Khan Research Laboratories (KRL) in Kahuta as the Additional Director Administration.

Safdar Nawab lived to the age of 94. He left behind a record of endurance, of a man who stayed present in his own life while being forcibly removed from it. Of a man who, stripped of movement and agency in captivity, did the only thing he could: he wrote himself home.

The writer is a member of staff. He can be

reached at hasnain.nawab1@gmail.com

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 25th, 2026