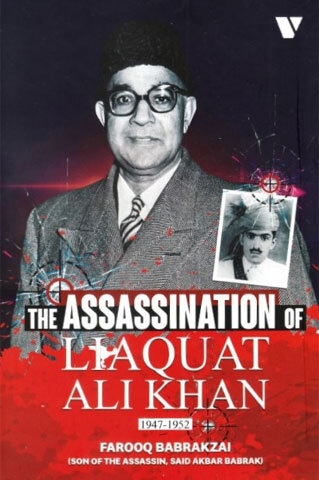

THE ASSASSINATION OF LIAQUAT ALI KHAN

In a mystery, the sleuth must be believably involved and emotionally invested in solving the crime.

— Diane Mott Davidson

On Tuesday, 16 October, 1951, around 4 pm, the first prime minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan, was going to address a public meeting in Company Garden in Rawalpindi. As he walked to the microphone and uttered the words“Baraadaraan-i-Millat” [Brothers of the Nation], a man named Said Akbar, sitting on the ground near the dais, fired two bullets at him in rapid succession with a 9mm semi-automatic pistol.

Chaos and mayhem suddenly erupted in the meeting. Khan Najaf Khan, the Deputy Superintendent of Police who had personally supervised the security arrangements, yelled in Pashto, “Who fired the shots? Shoot [him]!”. Within seconds, a police inspector, Mohammad Shah, came running with his service revolver drawn and shot Said Akbar five times at close range, in such a haphazard manner that he missed one shot altogether.

As Said Akbar was lying on the ground dying, he was also stabbed more than 26 times with spears by Muslim League volunteers. The recording equipment of Radio Pakistan was on and captured the sounds of the firing and the chaos for one minute and 13 seconds, and then fell silent. The entire shooting episode ended within 48 seconds. The recording is available online. Liaquat Ali Khan was taken to the Combined Military Hospital, where he succumbed to his injuries.

The assassin, Said Akbar, was my father, who had come to Rawalpindi from Abbottabad on 14 October.

One of Pakistan’s founding fathers and the country’s first prime minister was assassinated at a public gathering 74 years ago. Despite the formation of an Inquiry Commission and two other police investigations — one by Scotland Yard — until today, there has been no satisfactory closure regarding those tragic events. Now, the son of the assassin has penned his own investigation into the events in the shape of a book, which provides, for the first time ever, his family’s perspective as well as delves into the weaknesses of the official accounts and spans Pakistan’s tumultuous history — from the first war over Kashmir, the Rawalpindi Conspiracy and internal friction within the new state’s functionaries. Eos presents, with permission, excerpts from The Assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan: 1947-1952 by Farooq Babrakzai, published by Vanguard Books…

INTELLIGENCE FAILURES

Neither the CID (Criminal Investigation Department) nor the police personnel had any prior knowledge of Said Akbar’s presence in Rawalpindi, let alone at the public meeting. All police and CID claims about keeping Said Akbar under surveillance in Rawalpindi for three days prior to the murder, upon close examination, turned out to be false; stories that were fabricated after the tragedy. No CID or police official was able to establish Said Akbar’s identity in the public meeting.

Soon after the incident, Inspector Abrar Ahmad went around checking hotels in Rawalpindi Saddar to see if Said Akbar had stayed in any of them, when, after two hours, he got lucky at Grand Hotel, where Said Akbar was staying. The hotel clerk immediately identified and confirmed that the body was that of Said Akbar, who was staying at the hotel. That led police to Abbottabad and, by nightfall, with the help of a few men from the neighbourhood, they arrived at Said Akbar’s home.

Said Akbar’s eldest son, 11-year-old Dilawar Khan, was with the father in Rawalpindi, and was sitting in front of him in the public meeting. He heard the shots and saw the prime minister fall. He turned around to ask father why the prime minister had fallen and what was happening and saw the chaos erupting and people attacking his father. He got scared and ran away, leaving his shoes behind.

The assassination of the prime minister was a sudden, unexpected and shocking event for Pakistan. In the days following the incident, when the police and the CID officials started to examine the circumstances of the crime, they had no prior information about the incident, no relevant intelligence reports, and no leads to follow.

COMMISSION OF INQUIRY

On 25 October 1951, the government appointed a ‘Commission of Inquiry’, consisting of Mr Justice Mohammad Munir, judge of the Federal Court, as the president, and Mr Akhtar Hussein, Financial Commissioner, Punjab, as his associate. The Commission examined 66 witnesses in 38 sessions, 23 in Lahore and 15 in Rawalpindi. Four months later, on 28 February 1952, the Commission submitted its report to the chief secretary, Government of Punjab. From the final version of the report, 73 names, clauses and sentences were omitted, mostly for security reasons. This obfuscated the report and made it look quite weak.

The Commission looked at five major factors to see if they had any bearing on the assassination. It examined at length various documents about Said Akbar, from January 1947, when he and his older brother, Mazrak Zadran, surrendered to the British authorities in North Waziristan, till October 1951.

These pertained to their detention under the Bengal Regulation III of 1818, which determined their official status, starting in British India and then in Pakistan, and records of all the places they visited in Pakistan. Nearly all of this was irrelevant to the tragedy in Rawalpindi as the Commission did not find any valuable clues in Said Akbar’s travels, his contacts with people, and his lifestyle.

Next, the Commission examined the security arrangements at the public meeting, the circumstances under which the prime minister was killed, and recorded statements by witnesses. In some cases, after much rambling discussions, the Commission concluded that certain CID and police personnel made false statements. High-ranking officials, such as Khan Najaf Khan, Deputy Superintendent of Police (DSP) Rawalpindi, gave evasive answers to questions of the Commission. It was Najaf Khan who suggested, supervised and approved the security arrangements at the public meeting.

Other officials either lied or gave exaggerated accounts to the Commission to protect themselves. Inspector Mohammad Shah, who had shot and killed Said Akbar, was not questioned by the Commission.

POSSIBLE MOTIVES

The Commission also examined possible motives for the crime. It considered three: first, that Said Akbar killed the prime minister in a fit of insanity, but could not find any evidence to support it.

Second, he did so out of resentment over the prime minister’s policy regarding Kashmir. In fact, some time in the summer of 1951, Said Akbar had volunteered to raise a lashkar [band of fighters], pay for their food and other expenses, and lead them in the jihad to liberate Kashmir, but the Commission considered Said Akbar’s offer a “hoax” and rejected it.

Third, that he did not like the un-Islamic lifestyle of the prime minister and because his wife, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali, did not observe purdah [veil] in public. But this also turned out to be a baseless story.

It then examined various theories of conspiracy to see if Said Akbar was part of any of them but did not provide details of any conspiracy and discarded each of them and, in fact, stated its inability to uncover any conspiracy.

Police searched Said Akbar’s home three times and took away all items they considered important, including books, documents, air gun, money, mother’s gold, photos etc. A summary of the items was given in the Inquiry Report.

The public was not satisfied with the findings of the Commission because it failed to fulfil its own mandate and provide transparent answers to the very questions it was tasked to investigate. The two important questions for which the Commission could not find answers were: what was Said Akbar’s motive? And if the murder was the result of conspiracy, then who were his accomplices?

POLICE INVESTIGATIONS

The task of the Commission was to examine the circumstances of the crime, and not to identify any individuals who might be implicated, because that was the task of criminal investigation by police.

There was only one police investigation conducted in 1951-2, in Lahore, when our family was taken there. We were kept there for about five months, during which time mother was questioned through an interpreter. It was this investigation that the Inquiry Commission alluded to but gave no details, as it was on-going at that time.

Scotland Yard’s official Cecil Edwin U’ren referred to the same investigation as “headed by Chaudhry Mohammad Hussein, Superintendent of Police, CID, Lahore, and his team.” He quoted extensively from the Munir-Hussein Inquiry Report, but did not include any information from Chaudhry Hussein’s report and, what is more, did not even discuss his own conclusion with him.

The public and the media raised further questions about the U’ren report. The prime minister’s widow, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali, strongly reacted to the U’ren Report and raised several questions, but no one in Pakistan, whether the police, politicians or journalists, provided satisfactory answers.

The report by Chaudhry Mohammad Hussein and his team allegedly got destroyed when the plane carrying the police Inspector General Etezazuddin, crashed in August 1952. But curiously, Scotland Yard’s official Cecil Edwin U’ren was given access to it in 1954-5. That is because the documents pertaining to the investigation were safe and available. All the statements about the documents being destroyed were deliberate attempts by the government to protect unnamed army officers and government officials, and divert public attention from the case.

MY INVESTIGATIONS

The Inquiry Report at best described the circumstances under which the prime minister was killed. It provided sufficient background information for me to see the gaps and discrepancies in the description of events and flow of information. The assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan was the result of a well-planned conspiracy by the plotters. Said Akbar indeed had accomplices in Abbottabad, in Rawalpindi, and right at the public meeting on 16 October, 1951.

This work is driven by numerous questions that are explored in the chapters of the book. These are questions that have been asked multiple times since 1951, but not answered truthfully. For example, why would Khan Najaf Khan yell an order in Pashto at the public meeting in Rawalpindi, to shoot the person who fired the shots?

How did Dilawar Khan, Said Akbar’s son, come up with the story that his father had seen Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi in a dream on 13 October, 1951, who told Said Akbar to kill Liaquat Ali Khan? In fact, it was the police who repeatedly instructed Dilawar what to say and how to answer investigators’ questions.

Because the police had to find a motive for the crime, they invented the story of Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi and put it in Dilawar’s head. The police created that story from a document taken from Said Akbar’s home during one of the searches, which had names of Muslim warriors, including Sultan Mahmud Ghaznavi, written on it.

Over the decades, the Liaquat Ali Khan murder turned into a mystery, the result of some deep-rooted conspiracy, which no one seriously attempted to solve. The major reason was the investigation report by Chaudhry Mohammad Hussein that was deliberately never made public, and no other truthful statements came from the government. The Munir-Hussein inquiry and that by U’ren of the Scotland Yard went in two different directions, while exploring the same incident.

The former did not answer the questions it formulated to explore. The latter concluded that Said Akbar committed the crime because he was socially isolated, void of any reasoning, and had inherited some kind of criminal genes.

For me, it has been like solving a dozen separate but related puzzles, in which each one the actors played different roles. But when connected, the small puzzles make a giant puzzle, one that sheds light on the dark corners of the tragedy and attempts to provide transparent answers.

KASHMIR AND SAID AKBAR

The goal of the book is to find the hard and transparent answers of the case in plain and easy language. It attempts to inform and educate the readers and let them rethink and have a fresh look at history.

It neither glorifies Liaquat Ali Khan as a martyr nor condemns Said Akbar as the assassin. Here Liaquat Ali Khan is presented as a politician who had both his loyal followers and rivals in the government, but he also committed blunders, particularly his decision to accept the ceasefire agreement in Kashmir, which also sealed his fate.

The prime minister was a refugee from India, and Said Akbar was a refugee from Afghanistan, who had no personal grudge against the prime minister and no motive to kill him. He had no cultural roots in Pakistan and was not savvy in Pakistani politics. But he became interested in the Kashmir war solely because the social and political atmosphere in Pakistan was awash with pro-Islamic and anti-Hindu speeches, media stories and Friday’s sermons in mosques.

The constant clamour of jihad to liberate Kashmir from Hindu-domination naturally influenced young Said Akbar, who had seen Kashmiri refugees in Abbottabad and the Pashtun tribesmen who went to fight in Kashmir.

Religion played a nominal role in Said Akbar’s life in Afghanistan as, over the centuries, Islam had been adapted and blended with Pashtunwali, the Pashtun code of social and moral conduct. Being a good Pashtun naturally meant being a good Muslim. In Pakistan, he became interested in religion starting in mid-1949 and began to learn about Islam, but his goal was personal and pragmatic, not scholarly.

He sought meaning in his life, to make sense of the social and political turmoil in Pakistan, and to understand the fervour of jihad in Kashmir through religion and Iqbal’s poetry. These provided the justification for jihad in a simple and pragmatic sense.

It is important to note that the ceasefire agreement in Kashmir came into effect on 1 January, 1949, and hostilities stopped. However, Said Akbar’s interest in jihad started in mid-1949. Curiously, this is also the period when Maj Gen Akbar Khan, ringleader of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy, first spoke openly about overthrowing Liaquat Ali Khan’s government.

Said Akbar knew many tribal fighters from his Zadran tribe, some of whom visited him. It was during this period that Said Akbar became acquainted with men who were active in the war in Kashmir, and those who hated the ceasefire agreement that the prime minister had accepted, and therefore lost the chance to march on to Srinagar.

Some of these people eventually persuaded Said Akbar, in the summer of 1951, to assassinate the prime minister and, in the process, became his accomplices and facilitators.

I have taken it upon myself as my moral and ethical duty to uncover the truth to the best of my ability. It is something that I owe to the people of Pakistan, to my family, and to myself, while living thousands of miles away in the United States.

THE RAWALPINDI CONSPIRACY

Political assassinations are well-planned, meticulous operations by the plotters, their accomplices, facilitators, and those who carry out the deeds. Secrecy is the key to the success of such operations. Whether the crime is successfully committed or it fails, the news, stories and conspiracies later become part of public discussions. The plotters and accomplices remain hidden from the public eye. That is what happened in October 1951.

The Rawalpindi Conspiracy was the first coup attempt to topple the government of Liaquat Ali Khan and eliminate him. But it failed. On 9 March, 1951, the ringleader, Maj Gen Akbar Khan, and his collaborators were arrested. That was because, earlier in February, an insider of Akbar Khan’s group, Inspector Askar Ali, CID Peshawar, informed I.I. Chundrigar, governor of North-West Frontier Province (now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), who informed the prime minister.

The documents of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy presented in the court showed that “late Hon’ble Liaquat Ali Khan, along with his personal attendants… would be called and cleared.” That is, arrested and executed. The list also included the name of the first Pakistani Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Gen Ayub Khan, who “was shocked that he was to be shot.” When the first attempt failed, many officers thought of taking a bold action.

In the second week of May (1951), Maj Hassan met some other officers in Rawalpindi who were also apprehending arrest, and there was some talk of confronting the authorities and taking some desperate step. But the idea was given up. There was no leadership, and the suspected officers were far too demoralised and isolated from the top command to undertake the dangerous course of mutiny.

The trial of those accused in the Rawalpindi Conspiracy started on 15 June, 1951 and, four months later, on 16 October, 1951, the prime minister was assassinated in the same city.

I came across the Munir-Hussein Inquiry Report (1952) in the Asia Collection of Hamilton Library at University of Hawai’i at Manoa, in 1998. Since 2007, I have read the Report many times and re-read parts of it more than 30 to 35 times, taking copious notes on small individual events. In the process, it started to dawn on me that there were discrepancies in the recording of many events.

In 2010, I bought a copy of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy. Many events described in the book coincided with changes in Said Akbar’s life, and some of the people mentioned in the book were also known to Said Akbar.

THE U’REN REPORT

In November 2016, I went to London to visit the British Library and Scotland Yard, looking for a copy of Cecil Edwin U’ren’s Report (1955). After a few days of searching, I was told that the report was in the National Archive. About a month later, the National Archive put the photocopy of the report on a website and allowed me access to it for a fee.

I finally downloaded a photocopy of the report as it was published in Dawn on 25 June, 1955, along with other related documents, and the response by Begum Liaquat Ali Khan, the widow of the prime minister to the U’ren Report. The report is a photocopy of the columns in Dawn and does not have chapters and page numbers.

U’ren concluded that Said Akbar alone plotted to assassinate Liaquat Ali Khan, and that no one else was involved in any conspiracy. His report exonerated the police officials, satisfied the politicians, but very cleverly avoided getting involved in the controversies of the case. He expressed sympathy with police personnel for the undue duty-related stress they had to suffer during the investigation. He spuriously questioned Inspector Mohammad Shah, who had shot and killed Said Akbar, and did not even meet Khan Najaf Khan, Deputy Superintendent of Police.

The only valuable piece of information in the U’ren Report was that the police investigation conducted in 1951-2 was not destroyed in the plane crash in August 1952, because U’ren was given access to it in 1954-5.

U’ren considered Chaudhry Mohammad Hussein a highly competent police officer, whose team had conducted the only criminal investigation of the case. However, he did not quote any information from Chaudhry Hussein’s report. In other words, the U’ren report did not uncover a single piece of fresh and relevant evidence. His own conclusion was based on evidence that was skewed and faulty and had no bearing on the assassination of the prime minister. In short, his conclusion amounted to another cover-up.

Epilogue

There are also other sides to the story. Journalists and writers continue to write on Liaquat Ali’s murder and narrate at length his life and achievements as prime minister, and how his widow, Begum Ra’ana Liaquat Ali, was later sent abroad as ambassador. But there has never been a shred of objective information about Said Akbar before October 1951, and about his family after that.

Hasan Zaheer, author of The Time and Trial of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy, stated:

In March 1995, I wrote to the former prime minister, Ms Benazir Bhutto, requesting permission to consult the official records of the Rawalpindi Conspiracy and related background materials for this study. I thank her for graciously acceding to my request.

I personally would like to examine the investigation report by Chaudhry Mohammad Hussein and his team and other related documents of the assassination of the prime minister, which have been collecting dust in some government archives. However, in the current political atmosphere of Pakistan and the fact that I am an American citizen, it would require authorisation by high government officials and sincere cooperation of others. Something I cannot count on.

I realise that certain events are described more than once in different chapters of the book because each chapter analyses one or more related questions of the case and describes the characters and the different roles they played in the tragedy. All events eventually culminated in the killing of Liaquat Ali Khan and Said Akbar in less than a minute.

The author is the third son of Said Akbar, the assassin of Liaquat Ali Khan, and was born in North Waziristan. He lived and studied in Abbottabad, Kabul, Beirut and Honolulu, where he completed his doctorate in linguistics. He has taught in Hawai’i, Muscat and Beijing and at the Defense Language Institute in Monterey, California. He currently lives in California in the US

Excerpted with permission from The Assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan: 1947-1952 by Farooq Babrakzai and published by Vanguard Books

Published in Dawn, EOS, December 21st, 2025